The meniscus plays an important role in the functioning of the knee joint. As cushioning pads between the shinbone and thighbone, menisci help absorb shock and distribute weight. However, tears or injury to the meniscus are common, especially among athletes and people involved in high-impact activities. Until recently, treatment options for meniscal tears were limited. But new meniscus repair systems are revolutionizing treatment and allowing more patients to heal from the inside rather than undergo partial or full meniscectomy.

Anatomy and Function of the Meniscus

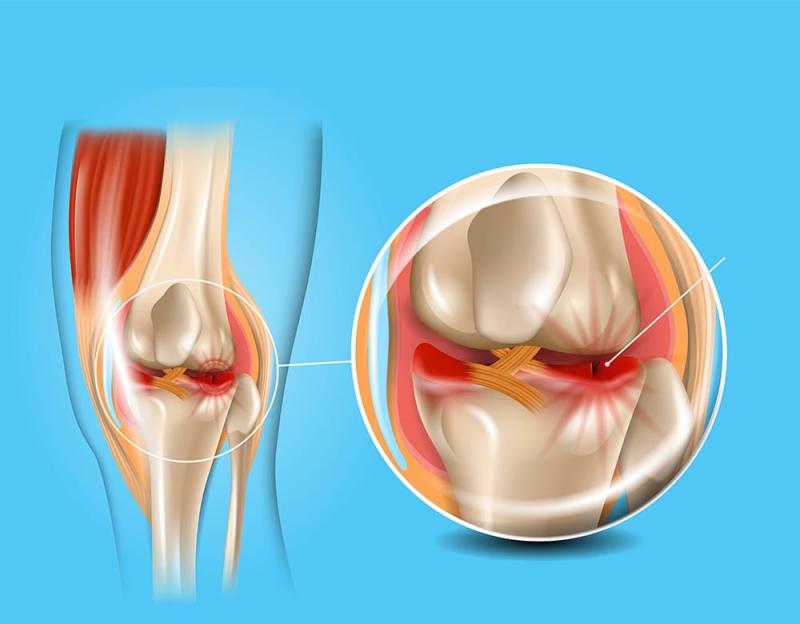

The meniscus is a C-shaped fibrocartilaginous tissue that sits on the surface of the tibia (shinbone). There are two menisci in each knee - the medial meniscus on the inside and the lateral meniscus on the outside. Together they deepen the trochlea of the femur and help stabilize the knee joint. The meniscus acts as a shock absorber, distributing pressure across the knee during activities like walking, running, jumping and landing from a jump. It also plays a role in lubrication and nutrition of the cartilage.

Common Types of Meniscal Tears

One of the most common forms of Meniscal tear is a longitudinal or bucket-handle tear. This occurs when there is an abrupt twist or torque on the knee that causes a portion of the meniscus to flip upwards or downwards. Other types include horizontal cleavage tears, radial tears (branching out from the center), and complex degenerative tears associated with aging or arthritis. Athletes participating in sports involving pivoting, twisting and sudden changes in direction are at highest risk of acute meniscal tears. Repeated microtrauma over time can also lead to degenerative tears.

Traditional Treatment Options

The gold standard treatment for meniscal tears for many years was partial meniscectomy or removal of the torn portion of the meniscus. This was done either arthroscopically or openly through a larger incision. While it provided pain relief, removing even a small part of the meniscus increased the risk of knee osteoarthritis in the long run due to reduced shock absorption and joint stability. For stable, contained tears in the vascular or red zone of the meniscus, repair was sometimes possible by simply debriding the tear edges. But extensive or complex tears extending into the avascular white zone could not heal on their own.

Advances in Meniscus Repair Techniques

New tissue engineering approaches and improved suture techniques are making it possible to repair more meniscal tears rather than remove torn segments. Some of the latest meniscus repair systems include:

- All-inside suture passers - These allow surgeons to place and tie knots completely inside the joint using small incisions rather than larger portals. This speeds up recovery.

- Bioabsorbable arrows/darts - Made of materials like PLLA, these pass through the meniscus and self-degrade after healing is complete, eliminating the need for knot-tying inside the joint.

- Fibrin clots - Applied as a biologic glue, fibrin clots can seal smaller peripheral tears, stimulate healing and help reduce pain.

- Biological scaffolds - Porcine or bovine meniscal scaffolds are being tested to replace massive tissue loss from complex degenerative tears. Seeded with the patient's own cells, these may regenerate new meniscal tissue.

- Growth factors - Various osteochondral factors like PRP, BMP-7, TGF-β etc. are being studied for their ability to enhance and accelerate the healing process when combined with standard repair techniques.

Outcomes of Modern Meniscus Repair

Several long-term studies comparing meniscus repair to partial meniscectomy have found that repair results in superior clinical outcomes for stable, contained lesions that can be surgically reattached. Post-op rehab is critical for repairs to incorporate and fully heal. While the repaired meniscus may not be as durable as normal, it continues providing mechanical function and prevents osteoarthritis progression for many years. Younger patients especially benefit from meniscus preservation techniques that could potentially save them from a full knee replacement later in life. Overall, the future looks bright for enhanced meniscal healing through innovative solutions.

In summary, advances in arthroscopic equipment, suturing techniques and tissue engineering have revolutionized the treatment of meniscal tears. What was once considered unable to heal can now often be repaired from the inside out. Combined with rigorous rehabilitation, meniscus repair allows more athletes and patients to retain their own cartilage and enjoy active, pain-free lifestyles long-term. As new scaffolds, growth factors and stem cell therapies emerge, we can hope to regenerate increasingly large portions of damaged meniscal tissue in the years ahead through minimally invasive means. This would help overcome limitations of current repair methods and better restore normal knee biomechanics.